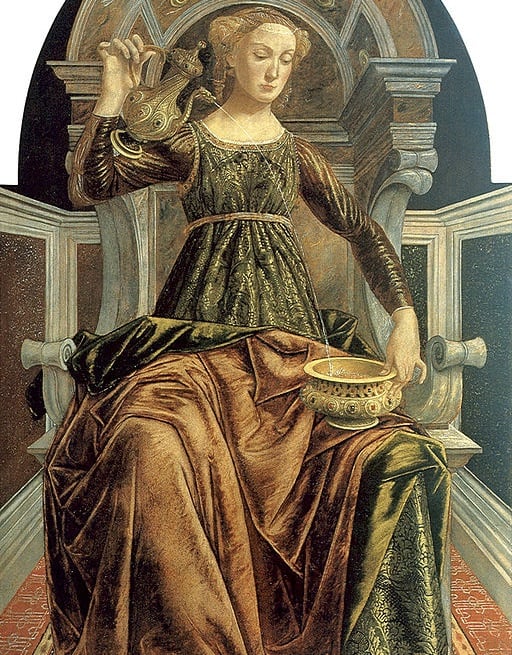

Temperance, Piero del Pollaiolo, 1470, detail [Public Domain]

During this Covid Advent and preparing for a Covid Christmas, I have discovered that temperance is probably one of the most under-practiced and undervalued virtues today. Most people think of the virtue of temperance as a fancy word for “moderation,” but that is not a full definition. Think about it: one is never allowed to sin in “moderation.” Imagine a husband cheating on his wife in “moderation”—I don’t think that would work too well for the wife.

What is temperance?

According to Aquinas, the virtue of temperance is the virtue that helps keep our senses in balance, particularly with taste and touch, that is, those things regarding food or sex (Summa Theologiae II-II,q.141 ar. 4). Notice that both food and sex relate to those things that create and maintain life itself—which is good—but when improperly they can become gluttony or lust. So yes, moderation is a characteristic of temperance, but it is not temperance itself.

Really, temperance is the virtue that directly helps us to overcome our concupiscence—our tendency toward sin—and our desire for more than what we need. In other words, temperance helps us actively separate out our wants—whether good or disordered—from our true needs. Food is a need, overeating or drinking is a want. Sex that leads to procreation is a need for the human race, sex outside the marital bond or closed to the possibility of fruitfulness through contraception is a (disordered) want. Consequently, such vices such as lust, gluttony, drunkenness, incontinence, curiosity, anger, and even pride can all fall under the category of vices opposed to temperance.

During these months of Covid, what was already blurred before in terms of needs and wants has perhaps for many of us become practically indistinguishable. With so many people being isolated and under extra stress due to quarantine and other restrictions, such things as pornography, gluttony, sloth, drunkenness, materialism, anger, and curiosity (Facebook, Twitter, 24 hour news, etc.) have skyrocketed. In short, concupiscence is running amuck, and only the virtue of temperance can keep concupiscence under control.

Saying no to the spoiled child

The reason why I am writing about this is because I have noticed my own complete lack of temperance during this time of Covid. To overcome any impure thoughts, I would eat something to distract myself, then grab a beer out the fridge so I wouldn’t think about sinful things. When I gave that up (gluttony), it would turn to anger and frustration because I know I cannot indulge in any of these habits. Finally, I would indulge in what St. Thomas Aquinas would call “curiosity” (Summa II-II q.167) by intentionally distracting myself on social media or binge-watching television shows. These vices are not separate vices but rather all came from the same source: intemperance.

“…intemperance, like an ill-trained and unruly child, is unreasonable headstrong, willful, wanting its own way, not knowing where to stop, and it grows stronger in its disgusting qualities the more it is indulged. Finally (and still like an unruly child) intemperance is corrected only by having its tendencies curbed and restrained” —Msgr. Paul J. Glenn, A Tour of the Summa (q 142 par 2; cf. Summa II-II q.142. ar. 2)

When I went to Confession last week, the confessor told me I was “immature” even though I am in my 40s. He was right, in the sense that I was being intemperate. I would simply jump from one vice to another and throw a fit, but not deal with the vice of intemperance directly. The minute I gave up one vice, like deleting my Facebook account, all the other vices became more attractive because it all came from the same source, concupiscence running amuck—and the devil, let’s give him some credit too.

The first line of defense against the sins of intemperance is fasting. Like an unruly five year old child, fasting puts concupiscence in a chair in the corner for a “timeout.” Those emotions and feelings then need to stay in “timeout” until they decide to behave in a reasonable manner. Prayer is not enough. Prayer is absolutely necessary, but alone it does not overcome the disordered desires of the body, i.e. concupiscence. We should pray to overcome the desire of intemperance, and when we do pray the Holy Spirit speaks to our conscience asking us, “Should I have another drink? Should I check out that website? Do I really need to buy that on Amazon?” However, in the end, we still need to make the choice. Free will is the gift God has given us that is entirely our own (Summa I-II q.9 ar.3,6), therefore we are responsible for our choices. But we are incapable of doing anything good without God’s grace (Summa I-II q.109).

Training in temperance

Fasting and prayer together help the choice to say “no” to little things to become natural to us, and therefore help us to recognize the difference between our true needs and our wants. Fasting, which leads us to the virtue of temperance, helps us to say “no” to some of those things that are still good for us, (this would be called the virtue of continence), so that when sinful things are presented to us it is much easier to say “no.”

During the rest of Advent and the upcoming Christmas season, pray for the virtue of temperance and say “no” to concupiscence—that spoiled child within you who wants everything. The more you empty yourself the more you can be filled with the Holy Spirit. A glass filled with sludge must be emptied first and cleaned before it can be filled with the fine wine of grace. Practicing the virtue of temperance by fasting empties the sludge, and prayer fills the glass with fine wine for our souls.

Oh, and one finally note: don’t let your little sacrifices go to waste— do it for the souls in Purgatory! There are plenty of souls in Purgatory who overindulged and could use some of that grace as well.

Beautiful new focus on Advent and Covid. Thank you.