Image: pages from the 14th century Gotha Missal [public domain]

Sacred language and Scripture

Jesus’s everyday language was Aramaic, although as a Jewish boy he would have learned to read and pray in Hebrew. Even as the Jews adopted the more widespread Aramaic, a language related to Hebrew, they preserved the Scriptures in the language in which God had revealed himself. It is not that they were completely against translations, as Jewish scholars produced the Greek Septuagint in Egypt, but they realized no translation could perfectly capture the meaning of revelation, because it was bound to the vocabulary and culture of the Hebrews. As the Italians say: traduttore, traditore—“to translate is to betray.” Preserving an ancient language also preserves the ideas, memories, and customs encapsulated by that language, elements that are essential to preserving a cultural and religious identity.

Greek was also a common language in Palestine during the life of Jesus. It was not a giant leap, therefore, for the evangelists and Paul to write in that language. This linguistic shift certainly also entailed inculturation, the use of culture to translate ideas and practices. Greek thinking met God’s revelation in the writing of the New Testament, a providential meeting of East and West in the ancient world. This first inculturation was so important for the Church that Christians even in Rome prayed in Greek for two centuries. Although Latin, ironically the vernacular of the time, eventually made its way into the liturgy, we still pray with remnants of the original Greek, especially Kyrie eleison, Greek for “Lord, have mercy.” Jerome’s vulgate translation of the Bible into Latin played a huge role in the inculturation of the faith for Roman Christians.

Sacred rites, sacred languages

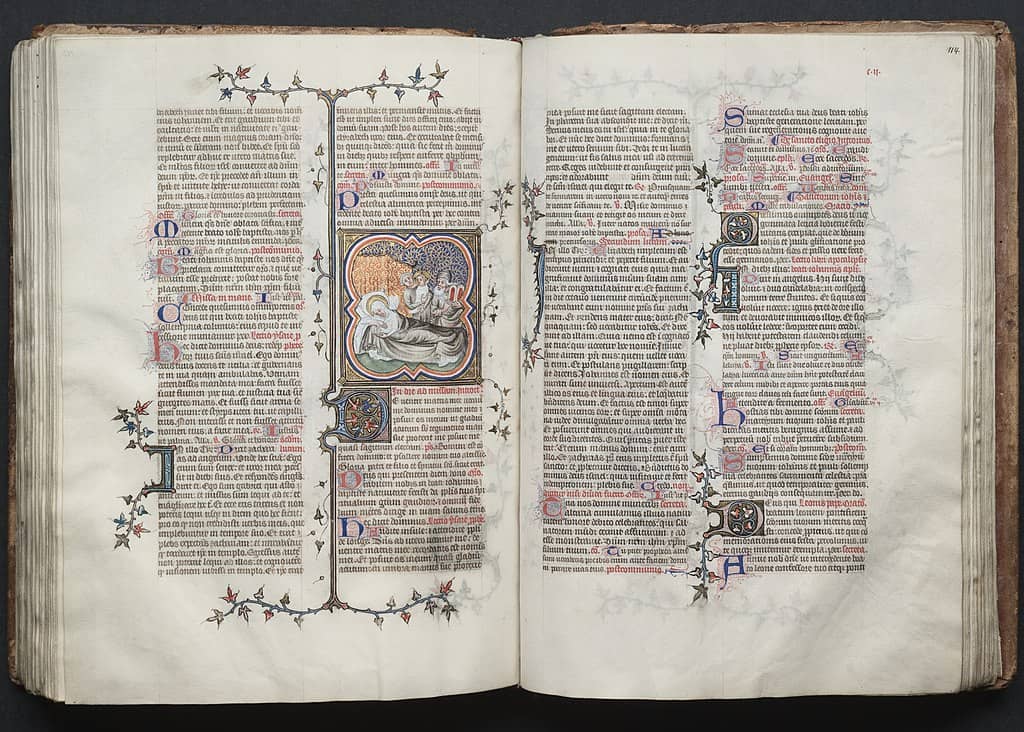

After the collapse of the Roman Empire in the West, Europe was overrun by barbarian tribes. Although some tribes had already embraced heretical Arian Christianity, others, such as the Franks and Anglo-Saxons, did not have a literate culture. Irish and Benedictine monks taught the English and Germans how to read and write not in their native languages but in Latin (although the monks did also preserve vernacular literature, such as Beowulf). The language of Rome, therefore, became their main legal, intellectual, and religious language. The Roman rite of the Mass, with its accompanying Gregorian chant, actually served as a unifying force throughout the empire of Charlemagne in the early ninth century, with a sacred language providing a common center for people of diverse cultures and traditions throughout Europe. The common thread of Latin assured that Catholics throughout the West shared a common theological vocabulary and ritual.

It is due to the conversion of the barbarians to the Catholic faith in the Middle Ages that Latin became the common sacred language for all Latin rite Catholics. The preservation of Latin, transmitting the legacy of classical and ecclesial culture with it through the ages, is more than an historical accident, however. Even the inculturation of the faith to the Slavic tribes in Eastern Europe, a bold and controversial move at the time, led to the sacred language of Church Slavonic, still used by Eastern Catholic and Orthodox faithful today as distinct from their modern, national languages. And Christians in Egypt pray in three languages, preserving Coptic (the ancient Egyptian language), alongside some remnants of Greek and the now dominant Arabic. Most strikingly, Maronite Catholics continue to use Aramaic, the language of Jesus, for the consecration.

Tradition and transcendence

Christians, like their Jewish forebears, preserve sacred languages because there is something deeply human about using a distinct language for prayer. Even though it is essential to be able to read the Bible and pray in our native tongue, the use of a distinct language for the most solemn moments manifests their transcendent importance. It also gives us precision for things like the form of the sacraments, as there have been recent tweaks to overcome imprecise translations. For instance, Pope Benedict XVI adjusted the words of consecration to “shed for you and for many” rather than for “all,” to match the words of Jesus. There has also been an uproar over changes to the translation of the Our Father in French and Italian. The use of Latin for our most common prayers provides stability through the constant developments of language.

Although the use of a sacred language may challenge us, since it requires us to learn basic prayers in another language, that can be a good thing. It requires more effort on our part that can help us to think through the meaning of the prayer so that we do not simply take it for granted. Using a distinct language provides a sign that the prayer is more important than the words of everyday life. Our Catholic schools used to all teach Latin for a reason (and most public schools did as well for cultural reasons). Learning Latin opens up the great heritage of the Church and the writings of the saints to us. Even just the basic vocabulary can enrich our understanding of doctrine and the Church’s liturgical tradition. Returning even to a limited use of Latin unites us to the past and would serve as a unifying factor for the Church. Even in the modern world, sacred language has not lost its relevance.