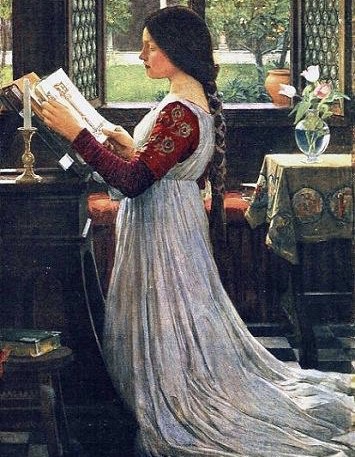

Image: John William Waterhouse, The Missal, 1902 [Public Domain]

In giving the technical definition of the virtue of humility, the Catholic Encyclopedia writes, “Humility signifies lowliness or submissiveness and it is derived from the Latin humilitas or, as St. Thomas [Aquinas] says, from humus, i.e. the earth which is beneath us. As applied to persons and things it means that which is abject, ignoble, or of poor condition…Humility in a higher and ethical sense is that by which a man has a modest estimate of his own worth, and submits himself to others.”

Virtue of dependence

Essentially, humility is the virtue that restrains the movement of the mind towards some excellence, particularly restraining the mind from thinking one is greater than one truly is before God. Simply put, humility is the disposition to accept our impoverished dependence upon God. How does this work? Well, upon considering our defects, weaknesses, and countless errors, we ought to acquire a sense of something lacking in us: I’m not perfect!

Yet we can go one of two ways with this: become prideful and pretend that this impoverishment isn’t really the case, claiming that we’re perfectly fine—or become humble, wherein we can accept this impoverishment and subsequently give ourselves over to God. For we realize that we cannot help ourselves, neither in this life nor in our pursuit of Heavenly bliss, and so submit to His grace instead (the humble one also submits, for the sake of God, to the other authority figures that He has placed over one—Pope, local bishop, parish priest, spiritual director, confessor, parent, boss, coach, etc.). This realization serves as a pivotal movement towards faith because it removes the obstacle of pride that refuses to subject itself to God.

Know thyself

Given the nature of the virtue, it should strike us that humility requires an awful lot of honest self-awareness. St. Bernard of Clairvaux writes, “There is nothing more effective, more adapted to the acquiring of humility, than to find out the truth about oneself. There must be no dissimulation, no attempt at self-deception, but a facing up to one’s real self without flinching and turning aside. When a man thus takes stock of himself in the clear light of truth, he will discover that he lives in a region where likeness to God has been forfeited, and groaning from the depths of a misery to which he can no longer remain blind…How can he escape being genuinely humbled on acquiring this true self-knowledge, on seeing the burden of sin that he carries, the oppressive weight of his mortal body, the complexities of earthly cares, the corrupting influence of sensual desires; on seeing his blindness, his worldliness, his weakness, his embroilment in repeated errors; on seeing himself exposed to a thousand difficulties, defenseless before a thousand suspicions, worried by a thousand needs.”

A thousand complexities, a thousand anxieties, a thousand difficulties, a thousand weaknesses…life is like walking a tightrope sometimes! The humble man has this knowledge of himself, though, which allows him to recognize his impoverishment and subsequently reach out to God

Imperfect and perfect humility

From this self-knowledge, the saints see two stages of the virtue arise: imperfect humility stemming from a negative consideration and perfect humility from a positive. The negative consideration is of our sins and the way that they cut us off from the source of life. When we subsequently embrace humility, we do so only imperfectly because our humility pours forth from the realistic consideration of the self.

The positive consideration is then of greatness, the perfection of truth, beauty, and goodness that is God. Standing as nothing before this grandeur, how could this consideration bring anything but humility? When we embrace this humility, we do so perfectly because it pours forth from the realistic consideration firstly of God. However, although one be perfect and one imperfect, both stages are important in order to progress in the spiritual life. After all, the perfect passes through the imperfect.

Upon humbly accepting the depravity of our sinful condition and/or the transcendence of God, we subsequently cry out to Him with childlike dependence. We put aside our own ideas and for once let our Father in Heaven take care of us as He sees fit. And take care of us He does, as He exalts the lowly with the knowledge of His infinite love and mercy. As Christ said to the pridefully “enlightened” who refused to do penance, “I confess to Thee, O Father, Lord of Heaven and earth, because Thou has hid these things from the wise and prudent, and hast revealed them to little ones” (Matthew 11:25; Luke 10:21, Douay-Rheims).

To deny the impoverished sinful condition of ours that leads to humility is to deny the truth of the reality of our human condition. As the Apostle John wrote in his first letter, “If we say we have no sin, we deceive ourselves, and the truth is not in us” (1 John 1:8). Why else would we need a savior unless that which we need saving from is the unpayable debt of sin? Do we not petition the Lord in the Our Father to forgive us our trespasses? It is no secret or surprise to the humble one that in Christ’s declaration of the arrival of the Kingdom of God at the opening of His public ministry, the first imperative that He gave to us as our response was to repent. Thus the virtue of humility is to recognize and acknowledge the truth of who we are and where we stand in relation to God.

Want to learn more about humility and the other virtues? Registration is now open for The Art of Living.

Articulated beautifully… Never heard humility compartmentalize as imperfect and perfect humility. Absolutely makes sense. Blessings