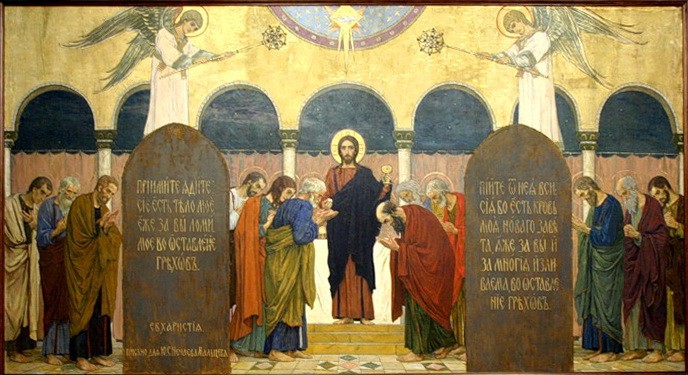

Image: Eucharist, V. Vasnetsov [public domain]

This is the fourth of a five-part series on exegetical proof for the Catholic doctrine of transubstantiation in the Bread of Life Discourse in John 6. Find Part 1 here, Part 2 here, and Part 3 here.

First Proof

I ended my last post with mention of the significance for transubstantiation in the Greek words used in the text of John 6. Prior to verse 54, esthio is the word used for “eating”, whereas Christ uses trogo there onwards. Esthio is used for normal human eating, while trogo is a more physical word describing the process of munching or crunching. This shift to a less common word which emphasizes the physicality of eating serves as one of the definitive proofs for transubstantiation in John 6.

Within John 6, esthio is used in verses 5, 23, 26, 31, 49, 50, 51, 53, and 58, and trogo in verses 54, 56, 57, and 58. Given their classical usages, trogo conveys a more crude and raw manner of eating than the more genteel esthio. While esthio is used metaphorically, trogo is not—it is rather a word tied to the physical process of eating food. Thus, the Catholic tradition recognizes the shift as Christ speaking of the physical act of eating, a real crunching of the teeth. Christ is demanding here that we express our faith by eating, in a real and physical way.

This is repeated in an insistent and increasingly scandalous way for the hearers. Some Protestant commentators argue that such a shift in words should not be overemphasized, for esthio and trogo are interchangeable and not as distinct in usage, referring as support to John’s citation of Psalm 41:9 (Septuagint) in which trogo is substituted for esthio. However, such objections ignore that esthio is used elsewhere in John without any appearance of trogo, while trogo only occurs in Eucharistic contexts, both in the Bread of Life discourse’s Eucharistic overtones and in the Septuagint citation itself, used by John to describe Judas’s eating at the Eucharistic Last Supper. The Greek words used thus clearly point to transubstantiation with a real physical eating to occur, trogo not carrying any metaphorical or symbolic connotation.

Second Proof

Two further proofs for transubstantiation next arise in verses 53-54, which relate the necessity of consuming Christ’s flesh and blood after the Jews question His ability to give His flesh to eat (vv. 52).

Firstly, as Wiseman writes, one must determine if Christ is speaking literally or figuratively: “If the phrase to eat the flesh of a person, besides its literal sense, bore…a fixed, proverbial, unvarying, metaphorical signification, then, if he meant to use it metaphorically…he could use it only in that one sense; and hence, our choice can only lie between the literal sense and that usual figure.” Wiseman further shows that in Biblical phraseology, the common language of those still living in the same region, and the language of the Jewish culture, the phrase possesses a figurative signification nonsensical within the discourse.

Concerning Biblical phraseology, the figurative sense occurs in the Old Testament in Psalm 27, Job 19, Micah 3, and Ecclesiastes 4, with all conveying a sense of injury, especially by calumny. Galatians and James bear similarly negative New Testament connotations of the figurative sense. Of the common language of those still living in the same region, Wiseman writes that Arab language and literature, inheritors of the Jewish land and dialect, likewise convey calumny when the phrase is used figuratively. Lastly, the languages of the Jewish culture, Aramaic and Syriac, also use the phrase figuratively for false accusation and calumny.

Thus, should Christ be speaking figuratively, He must be doing so according to this singularly defined metaphor with calumnious connotations, by which the listeners were being exhorted to commit calumny against the Lord. Therefore, the literal interpretation lending to transubstantiation is the only plausible determination.

Third Proof

Finally, verses 53-54 introduce blood, bread having only previously been referenced. This reference to blood is not only out of place if the discourse concerns faith and nothing sacramental, but furthermore the mere mention of drinking blood would have scandalously evoked laws forbidding such (Leviticus 3:17; 17:14; Deuteronomy 12:23). The importance of blood is seen in its role in the Levitical sacrifices and as a symbol of the familial bond between God and Israel in establishing the Mosaic covenant.

Christ would have also scandalized the Jews given the place of drinking blood in cannibalistic pagan fertility rituals. In fact, the crowd does interpret Christ in cannibalistic terms, leading disciples to leave Him (John 6:66)—something unprovoked was Christ speaking figuratively—and the Jews to conspire to kill Him (John 7:1). Transubstantiation is the only rational explanation for introducing blood given the opposition Christ would have known was to transpire.